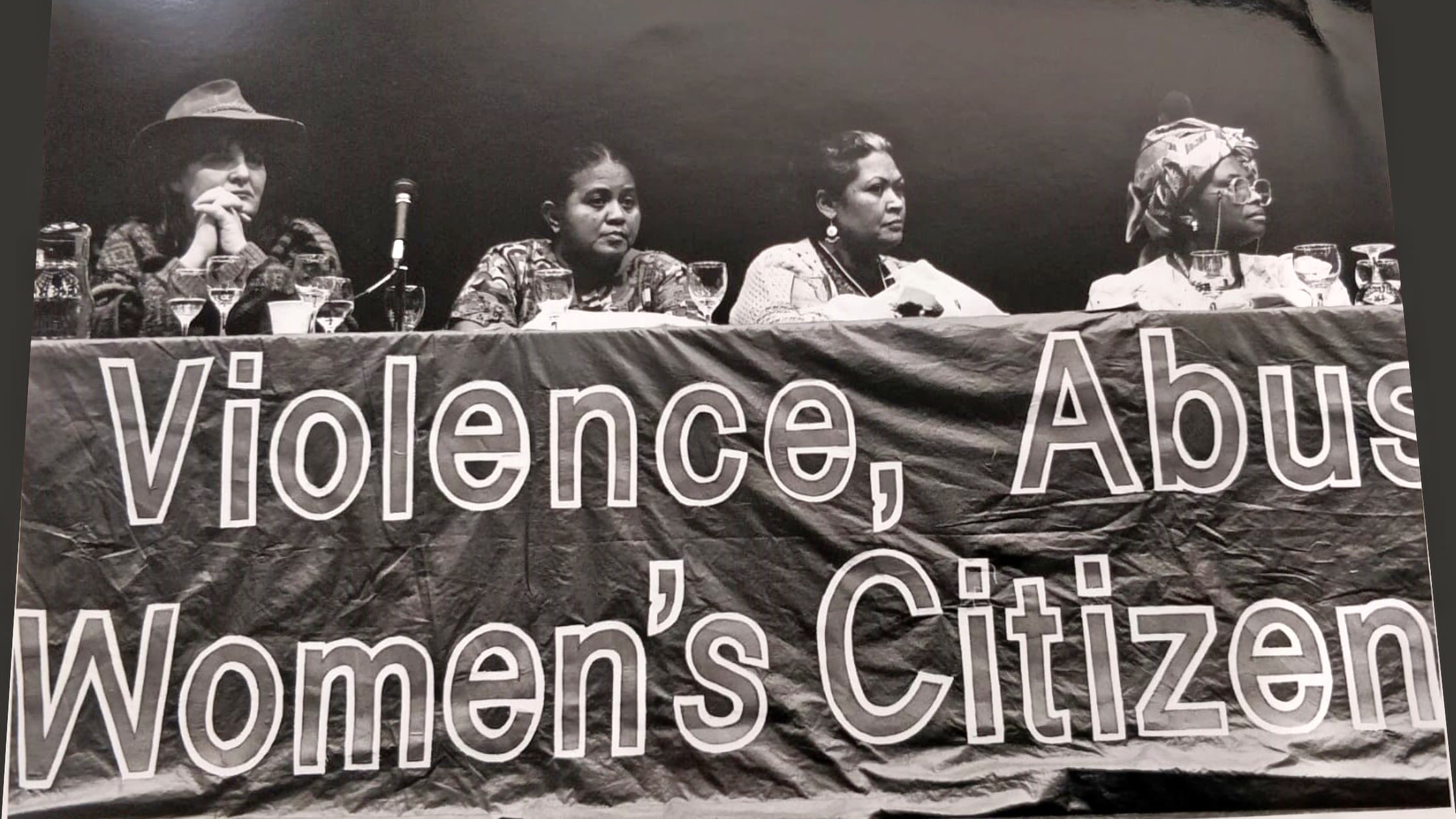

FiLiA Presents the Violence, Abuse and Women’s Citizenship Conference of ’96

The resilience and courage of the International Women’s Rights Movement in the 90s is retold in this unique exhibition retelling the Violence, Abuse and Women’s Citizenship Conference of ‘96. Feminists including Andrea Dworkin, Phyllis Chesler, Norma Hotaling, Jalna Hanmer, Sheila Jeffreys, Janice Raymond and Teboho Maitse attended and, for the first time, women from across the world came together to form alliances.

The International Conference on Violence, Abuse & Women's Citizenship was held 20 years after the first ever event of its kind - 'the 1976 International Tribunal on Crimes against women'.

It was April 1996. I was 34 with 17 years of lesbian, feminist and political activism already behind me, and I was feeling more tested than I could remember. ‘You are walking into the conference centre and are stopped by a number of male and female protesters, holding placards and banners, and shouting through loudhailers that the conference is racist, because it is against “cutting” (FGM). How do you respond?’

This was the question put to me by Jalna Hanmer, Professor of Women’s Studies at Bradford University, who was leading the job interview. I had applied for the position of Press Officer for the conference planned to take place in November later that year in Brighton. I lived in London, but the job would be based in Bradford, which meant a long commute. I answered, ‘I would tell them that female genital mutilation (FGM) was child abuse, and another religion, race or ethnicity has nothing to do with it. It is about the control of female sexuality.’

I got the job.

I had known Jalna since moving to Leeds at the end of 1979, when she was already a legend. I moved to London in 1987 but remained close friends and feminist comrades with many of the women there. Jalna was a goddess admired from afar. She was too busy to take much direct notice of who I was and what I was doing, but nevertheless, I had been in several of the groups she had set up over the years, and of course, I hero-worshipped her, as most feminists did.

The conference was the brainchild of Jalna and her colleague Cathy Itzin, who were motivated to push back against the anti-feminist atmosphere of the 1990s.

Feminism within academia was on the decline. Queer theory and postmodernism were beginning to dominate what used to be women’s studies, but Jalna was holding on. Activism was being replaced with the corporatisation of what had been the women’s liberation movement and the equality agenda, which was becoming more prevalent than the demand to end patriarchy. The conference was an antidote to that professionalisation and depoliticisation of what was becoming known as ‘the women’s sector’.

Radical feminists have long fought for revolution and to do away with sex stereotypes so that eventually, the concept of ‘gender’ (by which I mean sex stereotypes and a set of imposed rules as to how women and men are supposed to behave) would be eliminated. We recognise that men have power over women, and this has shaped personal relationships as well as every institution and every facet of social and political life. The world we seek would be dramatically different on all fronts. It would not be defined by the dynamic of domination and subordination, and all hierarchies would be challenged.

Conversely, liberal or ‘equality’ feminists are striving to preserve the patriarchal status quo but afford more ‘rights’ for women within that system. This means a focus on issues such as the pay gap, which has always been far more palatable for men than being told they are responsible for their own behaviour. Thorny issues like rape and domestic violence could be put to one side when they should be at the centre of such analysis, and liberal men could applaud equality feminism because it would be less threatening to their rights or power.

What had been a growth period within the women’s sector was becoming professionalised as a result of Thatcherism, and as a result, it became pretty much impossible to afford to go to university on a grant and do political activism unpaid, and many cutting-edge roles became salaried positions and were effectively defanged.

In the meantime, with the idea of laddism growing out of anti-feminism, sexual harassment and violence were as prevalent as ever, and although great strides had been made to improve policing under the criminal justice agencies, things were still pretty grim. So-called ‘date-rape’ drugs were on the rise, and there were calls to have a two-tiered system when it came to sexual assault, with ‘date-rape’ seen as a lesser problem than sexual assault by strangers. It was the very opposite of what feminists had been fighting for.

While Justice for Women and Southall Black Sisters were running impressive campaigns to highlight the huge problems within the justice system, we often felt like we were fighting a losing battle.

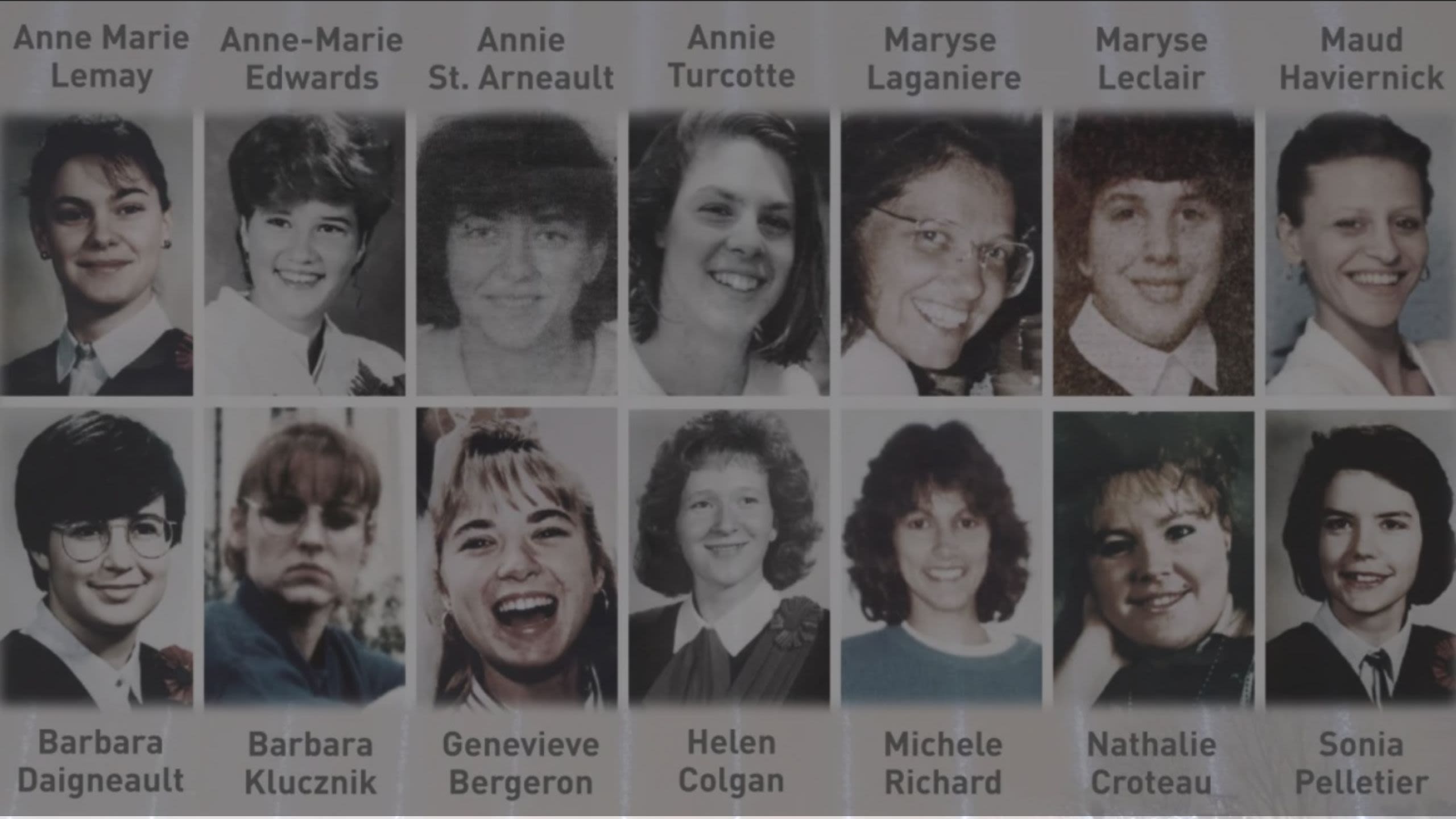

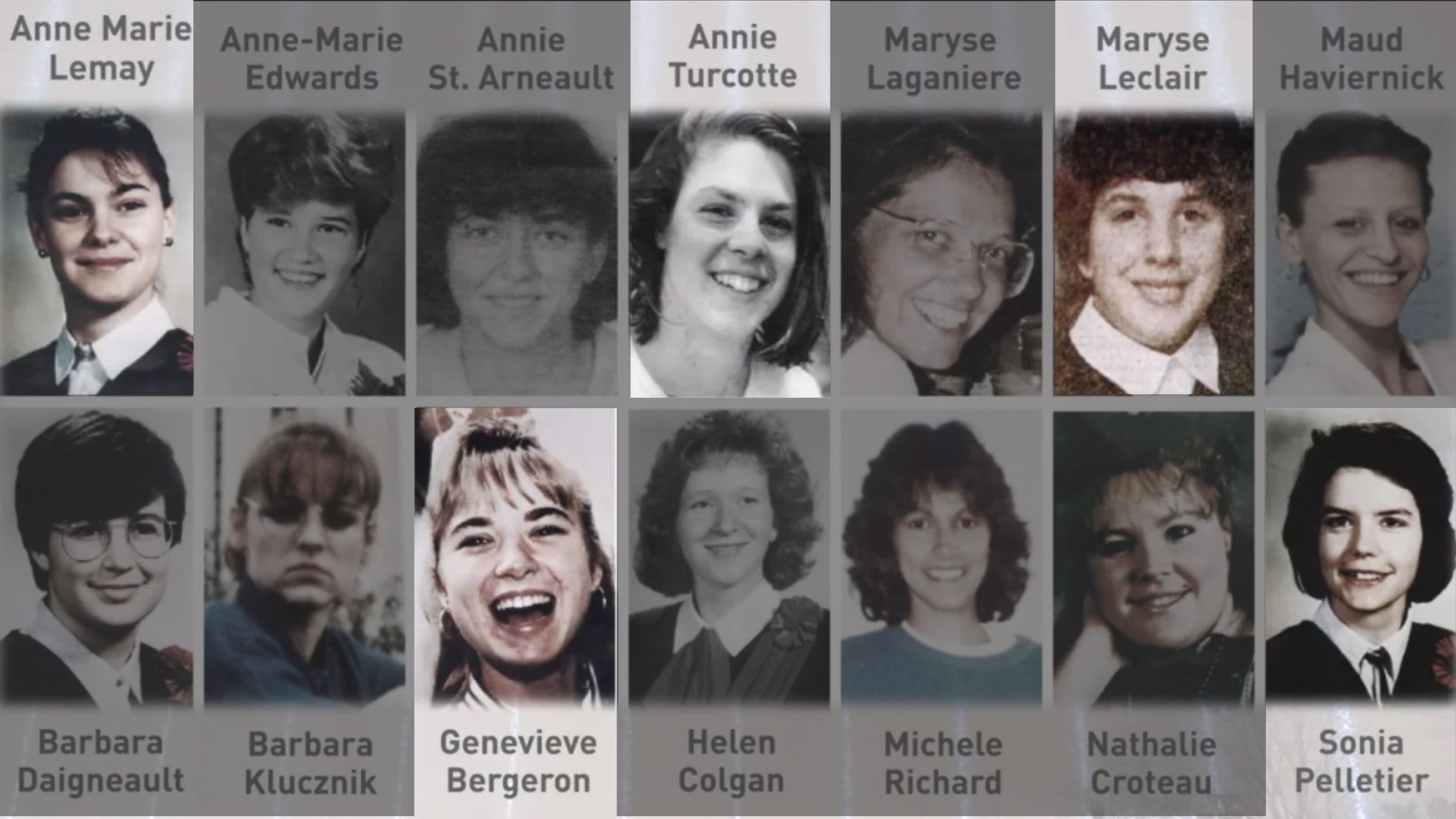

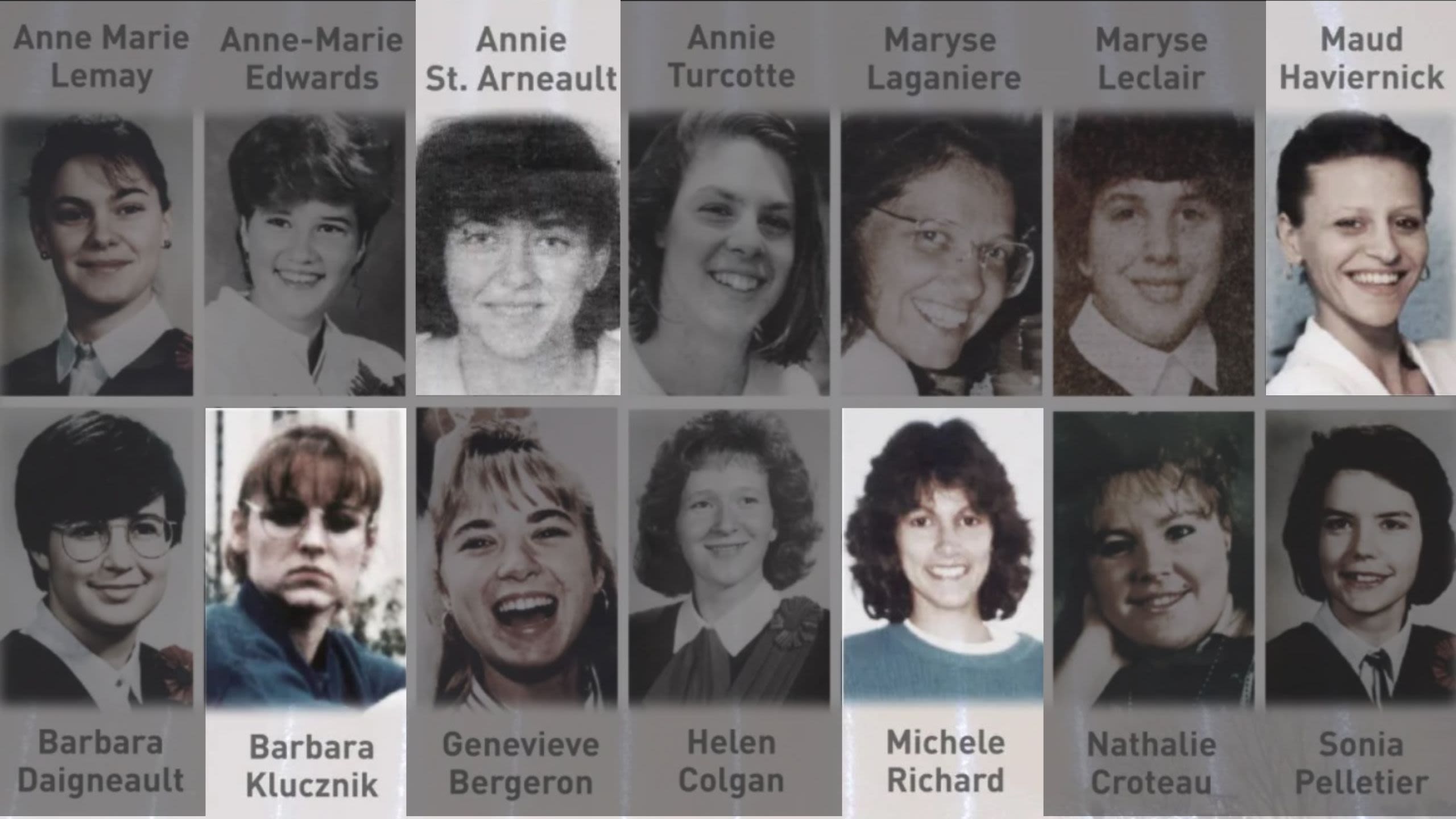

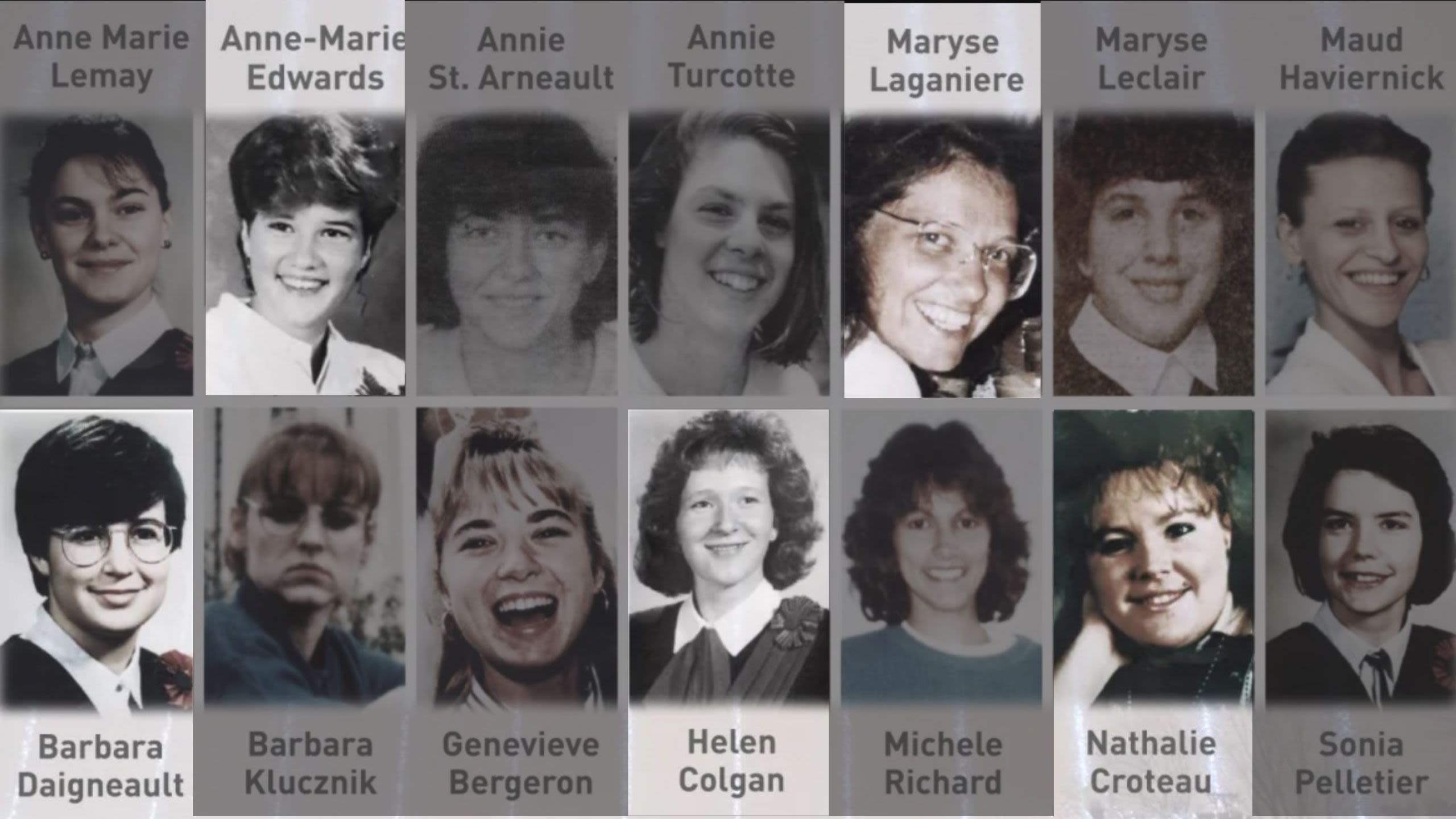

The global women's rights movement was also still reeling from the Montreal Massacre, which had occurred only seven years earlier.

On 6 December 1989, a young man brandishing a firearm burst into a college classroom at the École Polytechnique in Montreal, Canada. The 60 or so engineering students there had little time to react before the men were ordered from the room, and the gunman began shooting the women. Fourteen women were murdered; another ten women and four men were injured.

The killer was armed with a legally obtained Mini-14 rifle and a hunting knife: he had earlier told a shopkeeper he was going after ‘small game’. It later transpired that the killer had previously been denied admission to the École Polytechnique and had been upset. Before he opened fire, he shouted ‘You're all a bunch of feminists, and I hate feminists!’ One student, Nathalie Provost, protested ‘I'm not feminist, I have never fought against men.’ He shot her anyway.

"My name is Susan La Plante-Edwards, and I'm new on the feminist picture. At least, I was always a feminist, but I became an activist overnight, when my little daughter was one of the fourteen young girls who were killed just because they were women, and because they wanted to become engineers."

Liberal feminism was on the rise, with the sex workers’ rights movement beginning to emerge in countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and North America.

This movement draws a clear distinction between ‘sex work’ (empowered, chosen, non-violent) and trafficking (disempowered, forced, violent). It supports the removal of all laws pertaining to the sex trade, including pimping, brothel owning and sex buying.

There were also rumblings of discontent about the conference being held in England from, for example, the Scottish feminists, led by the redoubtable Jan McLeod – who complained that we hadn’t understood enough that Scotland had a different legal system to that of England and Wales, and why hadn’t we invited a keynote speaker from that nation? Similarly, some of the Welsh feminists were demanding materials in the Welsh language, which we just could not stretch to. The campaign to free Emma Humphreys had also come under such pressure from Welsh activists, who said we should have bilingual posters and campaigning materials. We didn’t think that was practical, and in any case, we could not afford it.

There were also a number of other phenomena that cried out for a global response – including trafficking and the emergence of reproductive technologies, which would clearly have a disproportionately negative effect on women in the global south. FINRRAGE (Feminist International Network of Resistance to Reproductive and Genetic Engineering), an international network of feminists who are concerned with the development of reproductive and genetic technologies and their effects on women, had been founded in order to put the spotlight on developments such as in-vitro fertilisation, embryo transfer, surrogacy, sex selection and determination, research and reproductive cloning, and genetic screening and manipulation.

My partner, Harriet, was put on security duty to look after Andrea Dworkin, who, understandably, was terrified of being physically attacked.

She had refused to stay at the same hotel as the other speakers and organisers because she was nocturnal and a recluse and could not face the constant stream of women approaching her, wanting to tell their own tales of violence and abuse. ‘It drains the blood out of me’, Andrea would later confess to me.

"We're a political movement. That's what we're supposed to do. We're supposed to find a way to stop the batterer, and protect the dignity of the woman's life. We may not accept the social situation the way that it is. We cannot accept the legal system the way that it is. And so we need to understand the reality for women on the ground, in the world, in real life. And our advocacy of social policy and legal reform has to be based on the experiences of real women. Which is why the research that's been done here is so very, very important."

A key aim of the conference was to revitalise - add new blood - to the movement to end male violence.

I remember the first morning of the conference when registration opened at 8 a.m., and volunteers braced themselves to greet the 2,500 people (mostly women) registered to attend. In the press office, we were focused on attracting media interest to the numerous issues that would be raised. The 137 countries represented at the event spanned every continent, and many delegates had never before left their country of birth.

It was of the utmost importance that connections between forms of male violence, abuse and oppression were made in a feminist context whilst at the same time recognising the significant differences between different cultures and nations.

The overriding atmosphere, although often charged with conflict ‒ and sometimes distress at the horrific stories of men’s violence ‒ was of solidarity between women. Although many of the speakers and delegates had big reputations – some were well-known authors and public figures – a wide spectrum of women attended. The fact that academics were in a minority was particularly refreshing, and in the main, they were there as activists rather than as scholars.

The sharing of global perspectives involved a huge learning curve, but the high level of motivation among the women to do something to make change happen meant that the atmosphere was, despite the disagreements and tensions, in the main positive and affirming of the power of feminism.

We had chosen the Brighton conference centre because of its scale, and because it was advertised as fully accessible for women with disabilities. On the first day, we had a summit from Sisters against Disablement, who insisted that some areas of the centre were difficult to get around. When Hilary McCollum, another of the organisers, said to them that she understood about women with disabilities and the constraints they faced, they shouted at her: ‘We hate that language; we are disabled women.’ I tensed up, waiting for the angry response, aware that Hilary worked at a local authority in London and knew of what she spoke. ‘OK,’ said Hilary, ‘but the terminology changes every few weeks so we can’t be blamed for not knowing what the latest is!’

The issue of terminology was a recurring theme at the conference: a Black women’s caucus discussed whether or not women from South Asia should or could use the term ‘black’ – or should that be the specific domain of women of African descent? Similarly, the term ‘incest’ was debated – with many of us disliking the term because it removed the abuse element and could be simply describing consensual sex with a blood relative. All of this was up for grabs, including an ongoing debate about how transient or enduring social class is.

From day one, there were calls to the press office that were so offensive, we could only laugh in disbelief.

I remember one women’s magazine asking if I could put forward ‘five or six African women who have been raped in black taxis in London during their visit to the UK’.

Most wanted gratuitous stories of victims, and few were looking for a broad angle about violence against women and the global movement to end it. I was eventually able to get interest from some serious journalists who published brilliant articles, with some even mentioning the underlying cause of male violence: women’s oppression under patriarchy.

Given that attendees were aged between 17 and 70, there were surprisingly few serious inter-generational disagreements, but a lot of mentoring. Groups of feminists would sit around drinking beer or coffee between sessions, talking about what had changed since the beginning of the WLM, and what still needed to change. There were many conversations about direct action: WAVAW (Women against Violence against Women), founded in 1980 at the Sexual Violence against Women conference in Leeds (with other local branches soon forming in locations across the UK) focused on exposing the misogyny of pornography; the reality of the sex trade; rape; and femicide. Around the same time, a direct action group, Angry Women, attacked a number of sex shops around the country and then claimed responsibility by writing letters to the local press. The focus was on the culture of women hating which had, in part, been exposed by the police failures and irresponsible reporting during the hunt for a serial killer of women that the press dubbed the Yorkshire Ripper.

"There was a feeling... of women coming together across divides, with what we had in common, and trying to fight for what was right. We were talking about all the different forms of violence against Women. But also of Women organizing. The movement of Women's Liberation is all around the world, and Women are fighting back."

A Selection of Speeches from the Conference

Incest: Getting Our Own Back

The conference took place during a time when the identity of ‘survivor’ referred almost exclusively to women speaking out about having been sexually abused by men during their childhood. Louise Armstrong had written a very important book about this in 1978, entitled Kiss Daddy Goodnight, and followed it with a sequel, published shortly before the conference: Rocking the Cradle of Sexual Politics: What Happened When Women Said Incest.

Harmful Cultural Practices

When Mimi Ramsey, an Ethiopian feminist living in the US, spoke of surviving female genital mutilation (FGM) she brought her own experiences, as well as those of other women, into the room. Mimi, a nurse, spoke movingly of her conversations with the mothers of girls vulnerable to FGM. She also raged against the cultural relativism, or ‘reverse racism’ as she called it, of white people dismissing the atrocity as ‘cultural’.

Mimi acknowledged the fact that mothers are tasked with either directly carrying out the mutilation themselves or facilitating a third party to do so. But she reiterated that the practice is deeply patriarchal, as its purpose is to suppress female sexual desire and to assure future husbands that their wives will remain faithful.

“Please, it concerns all races, all women, and all men to get involved. Please don't say, "I'm white. It doesn't concern me. I'm Chinese, it doesn't concern me." Yes, this is about children. When it comes to, when it's children, it concerns all human beings, all races.”

Prostitution: Getting Women Out

Norma Hotaling spoke about running the very first ‘John School’, where police were encouraged to actively seek out sex buyers (referred to as johns in North America) and offer them a 12-week ‘re-education programme’ to teach them the realities of the sex trade and to explain the potential negative consequences for them if they were subsequently apprehended. Norma was a survivor of the sex trade. ‘We MUST tackle the demand, and get the women OUT’ she said, and received a standing ovation. Fiona Broadfoot, Irene Ivison and other abolitionists spoke in public for the very first time during those sessions.

"How are we trained to walk down the street and not see the women and girls crying out for our help? How are we trained to talk about prostitution through the eyes and the voices of the perpetrators? We call it women's rights, and women's rights is a wonderful thing to line up behind, right? Prostitution as a woman's right. But when we line up behind this, what are we really lining up behind? Aren't we lining up behind the rights of pimps? Of johns? Of traffickers? Aren't we saying it's their right to kidnap, to traffic, to use, to buy, to kill, destroy, and disappear hundreds and thousands, if not millions, of women and girls around the world? How are women trained never to see that there's a customer involved in prostitution? How are we trained never to talk about the men?”

Child Protection

Another keynote speaker was Beatrix Campbell, a journalist and activist. She spoke about the disaster of so-called ‘child protection’ since 1987, as a result of the Cleveland crisis. We have now come full circle; Bea will speak at FiLiA 2023, launching her new book on Cleveland.

Rape in Marriage

Just four years after rape in marriage was criminalised in England and Wales, a parallel session on the implementation of that law was both powerful and emotive. The fact that it had previously been perfectly legal for a man to rape his wife was described as unbelievable, and many women spoke about how sexual violence had always been part of domestic violence within marriage and other heterosexual relationships, though very few women would call it rape. A number of the women attending that session lived in countries where rape in marriage was still legal.

“We need to understand the reality for women on the ground, in the world, in real life, and our advocacy of social policy and legal reform has to be based on the experiences of real women.”

Building Coalitions

The session ‘Building Coalition in the Israeli Feminist Movement: a Grassroots, Multicultural Perspective’, was delivered by the New Initiatives by Women/Women’s Coalition. It was an important session for establishing the work between Arab and Jewish Women working to end male violence in the Middle East.

From the Cradle to the Grave

Clergy abuse was the subject of a harrowing session with Margaret Kennedy, in which the activist and scholar outlined her theory ‘From the Cradle to the Grave’ about children and women of all generations being targeted by priests and other religious men in positions of power.

Nationalism, National Liberation and Violence

Two sessions stood out for me. ‘Nationalism, National Liberation and Violence’ by Tehobo Maitse from South Africa. Tebs, as she was known, was one of Jalna’s PhD students, and I got to know both her and her work well in the months I had been based in the research unit. Tebs spoke of her work to end violence against women, exacerbated by the struggle for national liberation and the increased machismo women had to deal with from both sides of the divide.

“I believe that if during the process of struggle for national liberation from an oppressive and racist regime, women are still raped, molested, humiliated, tortured by men, then obviously there is something very, very wrong with the ethos of both nationalism and national liberation.”

Another was the keynote on the politics of women-killing. For many women, hearing the term ‘femicide’ for the first time was eye-opening. It had been coined by Diana Russell at the 1976 International Tribunal of Crimes against Women at which Jalna Hanmer had both spoken and, infamously, taken a group of women from local refuges to give personal testimony.

At the time of the conference, post-modernism was burgeoning within universities, and soon morphed into ‘queer studies’.

A number of sessions addressed this – such as what was termed on the programme ‘Choosing to be violated? The problem with defining lesbian sexual violence’ which was about the adoption by some lesbians of sadomasochistic practices, which we argued, came straight from gay male culture. There was also a session on the ‘lesbian sex industry’ because lesbians were beginning to produce and consume pornography and even justifying paying for sex with other women. At the time, the commercial lesbian scene that invited strippers and lap dancers to perform in front of women was in its infancy.

There was an argument about disability: some disabled activists said that deaf women had no right to use the label or identity, and some deaf women were offended at being labelled disabled.

One delegate complained that ‘no keynote sessions dealt with violence against lesbians’ but then acknowledged that issues facing lesbians had been dealt with and raised during several presentations throughout the week. There were also complaints from a caucus of Black feminists that were unhappy about there being no Black British keynote speaker; from some older women who felt the conference and associated facilities and activities were geared towards younger women; and a working-class woman who accused the organisers of being elitist and upper middle class. The event was not perfect, and this was acknowledged in private and public conversations.

But it was hardly a week of doom and gloom: there was no shortage of laughs throughout the week. When, in the packed café at lunchtime, a young, upper-class American follower of Charlotte Bunch decided to challenge Janice Raymond about remarks she had made on stage (that Bunch had turned to ‘pro-sex work’ in order to attract lucrative funders), Janice advised the young woman to ‘learn your history’ and not be so naive. She shouted back, ‘But Charlotte is the LEADER of the feminist movement!’ The look on Janice’s face was a sight to behold.

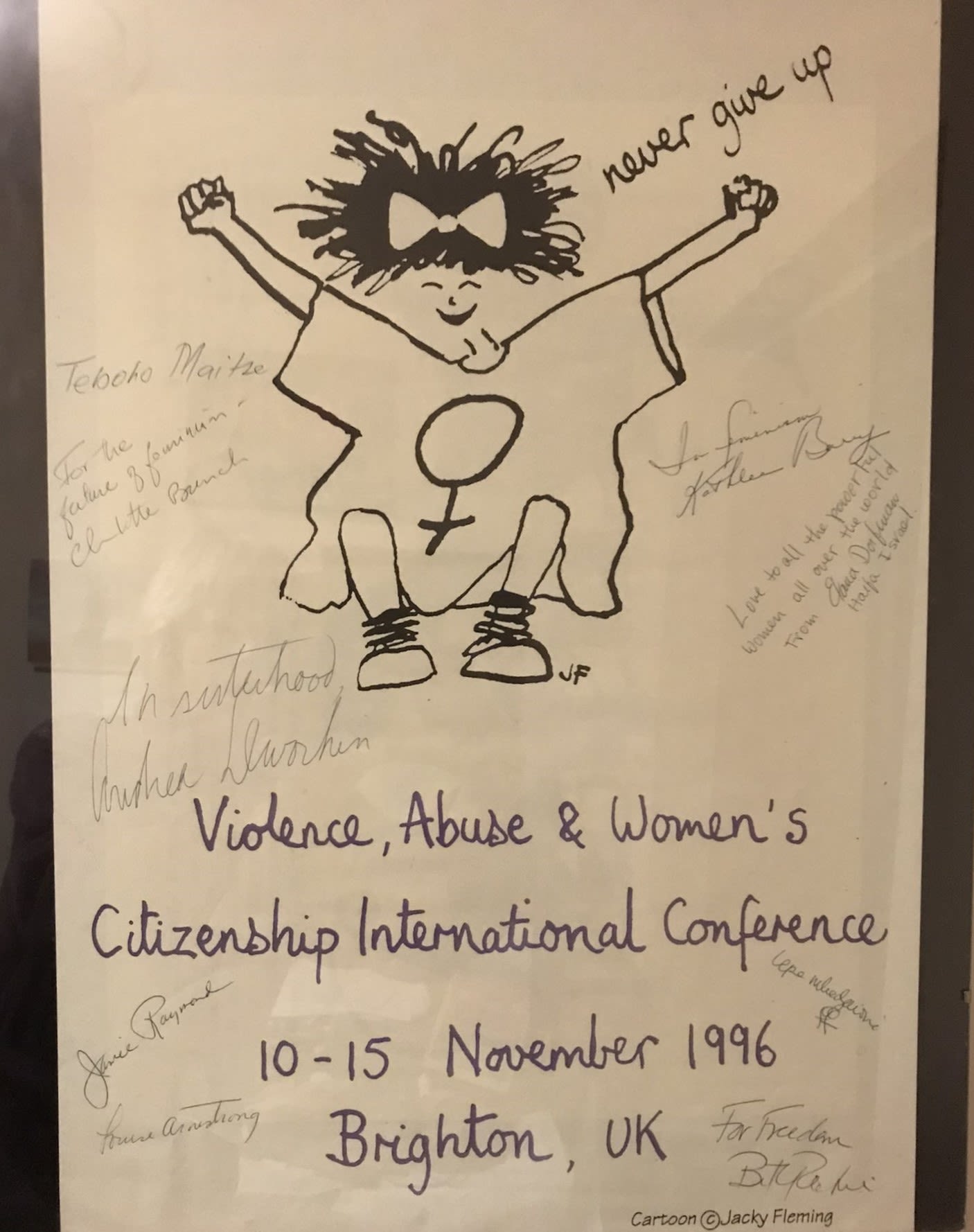

Jackie Fleming's 'Never Give Up' Cartoon, signed by conference speakers Tebaho Mohatse, Charlotte Brunch, Andrea Dworkin, Janice Raymond, Louise Armstrong, Kathleen Barry, Elana Dorfman and others.

Jackie Fleming's 'Never Give Up' Cartoon, signed by conference speakers Tebaho Mohatse, Charlotte Brunch, Andrea Dworkin, Janice Raymond, Louise Armstrong, Kathleen Barry, Elana Dorfman and others.

On the last day, following numerous presentations on pimping across borders (trafficking) and the harms of all forms of commercial sexual exploitation, a group of ‘sex workers’ rights’ campaigners from Europe turned up with the intention, we were warned, of planning to get up on stage to denounce the position taken by the conference on prostitution – namely, that the sex trade is a cause and consequence of women’s oppression and that paying for sex should be a criminal offence.

The all-female security team enlisted Jalna’s son Laurence to remove the steps leading up to the stage, in the hope that the agitators would assume he was one of the technical support contractors employed by the conference centre. It worked. The plenary speakers had entered the stage from the back, so there was no way for the ‘sex work is work’ lot to get up there. The conference ended on a high: the ‘sex work is work’ delegation left the conference, and the plenary session ended with a thunderous, cheering standing ovation for the organisers, speakers, and each other.

It is almost impossible to convey how important this event was for the international feminist movement.

It changed the lives of many of the women that came to the conference, including mine, as a result of having made connections between feminists from all over the world.

Hearing about different ways in which men violate women and girls, and all the inventive, courageous strategies developed by feminists to prevent such horrendous acts, was hard, but it did leave us all with a sense that we were a hugely powerful global movement at the same time. It also left images in my head that hadn’t been there before: I had watched a film of a seven-year-old girl being subjected to FGM; I had heard women describe what happens in the brothels of Bangladesh; and I had listened to women who had endured the most unimaginable torture at the hands of men only to bounce back and do the work that would prevent it happening to others.

I was committed to ending male violence before Brighton ’96, but afterwards I had renewed energy. I was to work with Jalna at the research unit in Bradford and subsequently Leeds Metropolitan University until 2000. The new friends I made in Brighton enriched my life. I am still close to many to this day, and there are a number whose obituaries I have written and had published in national newspapers. As for Jalna Hanmer - in coming up with the idea for the conference at a time when feminism was waning, she helped build a new and vital movement.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, feminism (by which I simply mean the social justice movement that focuses on ending men’s violence towards women in all its forms) had been waning. What Jalna and the Brighton conference did was to re-ignite that movement, and it has been proudly fighting for the liberation of all women everywhere ever since.